John Whitehurst was quite possibly the most creative and distinguished person that Derby has ever produced: it is perhaps a contest between only him, John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, Erasmus Darwin, who only lived in Derby for about twenty five years, and Joe himself. If we restrict the entries to only those born here, then Joe wins ~ John was originally from Congleton.

So who was he? He was twenty years older than Joe having been born in 1713. He had relatively little formal education as far as we know, but was taught the skills of clockmaking by his father, as this was his trade. Just after Joe’s birth in about 1736 he appears in Derby to establish himself. He must have had some sense that this town could provide him opportunity not only in clock and watch-making, but also in instrument making. As an ‘outsider’ he could not just set up in business against those already residing here. He could make clock-works, but only sell them in other makers’ cases. In an adroit move, he made a new town hall clock for the aldermen gratis, in return for which he was made a burgess of the town. By the late 1730’s he could trade and he could vote. From there, he never looked back. He could make barometers, hall clocks, thermometers, pyrometers, compasses, all sorts of contrivances for the movement and pumping of water, church clocks, air pumps ~ all manner of mechanical objects and he soon had a thriving workshop just a few doors up from the Wright household.

It was the sort of place that would fascinate a small boy and we can imagine that in the mid-1740’s as Joe was coming up to his teens, he might well, as the child of an important neighbour, be indulged with having a go at using offcuts and scraps under the eye of Whitehurst himself, or one of his tradesmen. When his niece was well into her seventies in 1850, or thereabouts, she produced a memoir of Joe from her dim remembrances of what she had been told about his childhood. She recorded that he had a great interest in all things mechanical and made various toys and gadgets. The example she cites is a model gun which was left behind when the family fled to Repton during the ’45 Stuart rebellion. As we have seen, Highlanders were billeted in the house and the gun was found, allegedly eliciting interest and admiration from the new arrivals who expressed a wish to meet the young gentlemen. However true or false this precise example may be, it would certainly be true that Whitehurst’s workshop would have been an absorbing place in which to spend time. All the machinery and instrumentation they produced was, of course hand-made and with great precision. There would have been cutting, engraving, forging, annealing, acid etching, glass grinding and lens-making, all using a wide variety of metals, and exotic substances like mercury, gold, enamels and caustics.

Whitehurst’s business and range of productions grew and grew as new industrialists needed new forms of instrumentation for their own productions. He made new types of pyrometers for Josiah Wedgwood’s kilns in Etruria near Stoke and swapped ideas with Matthew Boulton in Birmingham about coating metals, and myriad other mechanical and engineering problems in which they had common interest. With the addition of Erasmus Darwin, who was then a doctor in Lichfield, a coterie of like-minded men began to gather informally but regularly to present their current work and new developments. This, of course, became the Lunar Society which, over the fifty-odd years of its existence from 1765 can lay considerable claim to have led one major strand of the English Enlightenment.

There needs to be mention of one more of John Whitehurst’s many interests, and that is to do with what was to become his major publication: An Inquiry into the Original State and Formation of the Earth. This was really nothing to do with his day-job, but as his business grew to the point where he could hand over much of the day-to-day running to his nephews, (he had no children), freeing him to get off to the Peaks to take samples, look for fossils, classify rock types and, above all, get into lead mines to study the strata that were exposed by centuries of subterranean exploration. The great debate at the time as to the origins of the Earth was between the vulcanologists and the neptunists: had the Earth’s surface been principally formed by the effusions of lava and the upward forces of subterranean fire, or by the process of river and oceanic erosion and deposition? And how did these sea creatures end up in limestone and similar aged rocks? This problem absorbed Erasmus Darwin as well, and his grandson, Charles Darwin, given some heavy hints from Erasmus’s own writings, had something to say about evolution much later in 1859.

But a century earlier, Whitehurst, Darwin and Benjamin Franklin, who was resident in London as a diplomat for eighteen years between 1757 to 1775, were wrestling with these and a variety of other questions, and Franklin stayed with Whitehurst in Derby at least three times in that period. They were lifelong correspondents up to 1788 when Whitehurst died having spent the last fifteen years of his life in London where he had the key post at the Royal Mint overseeing the coinage.

So how well did Joe know him, and what sort of a relationship did they have? Well, it has to be speculative. I don’t know of any correspondence between the two, though there is the famous letter, (if you are a Wright obsessive as I have perhaps become), from Joe to his brother Richard from Naples in 1774 when Joe is describing his recent awe-inspiring trip up to the rim of Vesuvius: ‘When you see Whitehurst, tell him I wished for his company when on Mount Vesuvius, his thoughts would have center’d in the bowels of the mountain, mine skimmed over the surface only…’

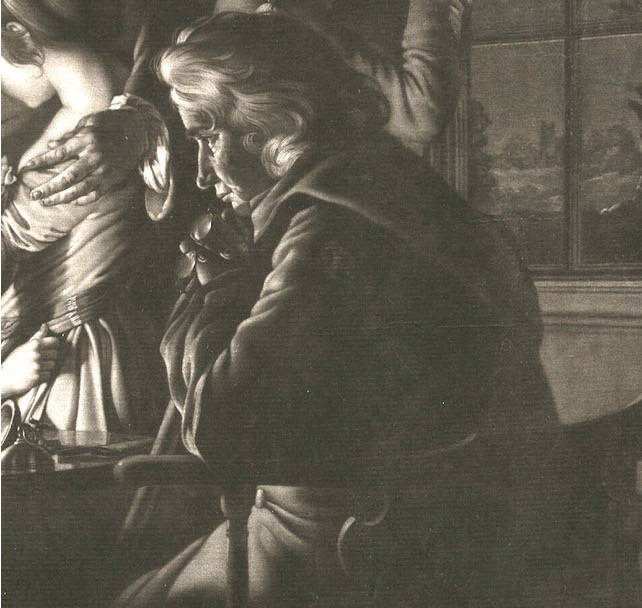

My sense of their relationship is that John was very much a mentor figure for Joe. If you dive into Painting Faces you will see that it opens with Joe seeking his advice on how he might avoid the fate his father has in mind for him to study for his articles in a law practice. Their discussion forms the first detailed exchange in the novel. It is entirely plausible that the childless John took a shine to his neighbour’s son and enjoyed his interest in the goings-on of the workshop. As the novel develops we see John advising Joe about being bolder in his career choices, investing time in understanding what’s holding him back and quietly urging him on. There has always been some suspicion that the magisterial figure in the Orrery was based on John Whitehurst and that possibly even the philosopher in the Airpump might also owe something to him. It’s all quite speculative. You could also make a case for the ruminative gentleman in the corner of the Airpump. Here he is in a print version. You can compare this (1766) with the portrait of 1784 above. Pretty close?

I create a whole chapter mid-way through the story where Joe, now approaching forty, joins John on the critical excursion of a few days to Matlock Dale where he finally resolves his last questions regarding his hypothesis on the Formation of the Earth. It is also an oblique means of getting introduced to the woman with whom he will elope within a year.

I also make John the father-figure of the tight-knit little group of rising young men in town: Joe, Peter Perez Burdett, surveyor and polymath, and Joseph Pickford, the architect. John presides at their supper club at the Old King’s Head where they swap news about their various exploits.

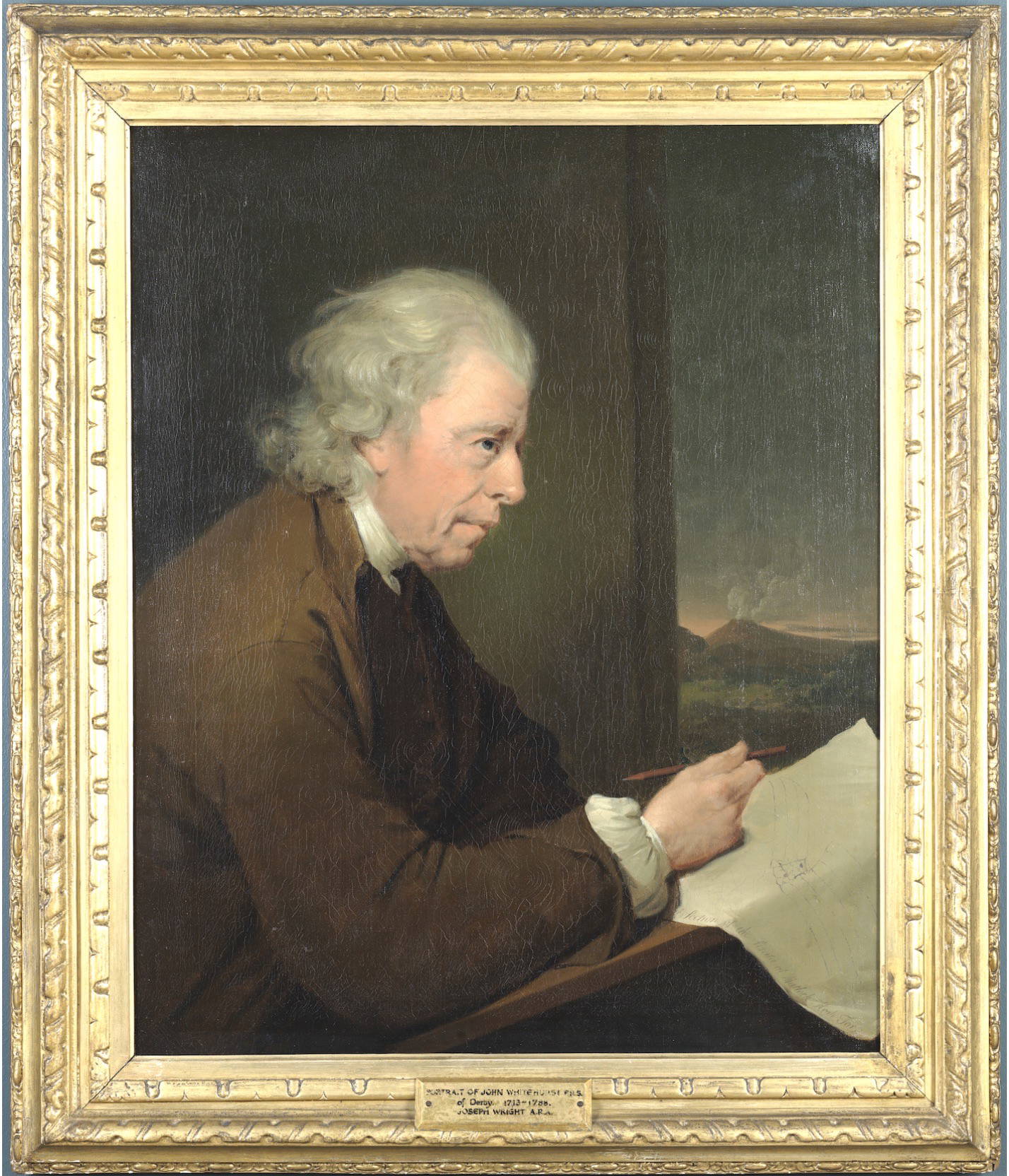

There is one fact that is incontrovertible about their relationship, and that is that Joe painted and gifted John his own portrait in 1784. It is a singular portrait, and not like any other that Joe produced. He makes John almost a medieval scribe sitting in his cell: he is pondering as he holds his pencil and works through some thought that is preoccupying him. On the tilted desk or drawing board is the well-known diagram from An Inquiry into the Original State and Formation of the Earth. It is a cross section of Matlock Dale and is strata which he had been able to define thanks to the extensive mine workings there. To his left there is a bare aperture in the wall ~ you can’t call it a window ~ and beyond a landscape with a gently smoking volcano, representative of the forces that John thought were the prime forces in the Earth’s formation. It is all strangely un-English. It is as though that view is symbolic of an aperture of the mind: John Whitehurst’s thoughts have brought it all into creation and explanation.

John passed through Derby that year, sent by the Royal Society to see the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim so that he might develop a wider explanation of his theory. That trip was probably the last time they met.

Portrait of John Whitehurst 1784; Derby Museums. On loan from Private Collection