Frankly, it was difficult. What were the barriers to becoming a painter or even more prestigiously, an artist? There was a difference between these two things. In Painting Faces, I imagine what becomes a rather heated and dangerous discussion between Joe’s painting master, Thomas Hudson, and the adolescent Joe in which Joe attempts to dispute this difference. Hudson, being at the very top of the painting profession as a portraitist of the great and good would not have considered himself to be an ‘artist’ in the sense that he had some inner thoughts he wished to convey nor a particular response he was seeking from his viewers. He was a professional face-painter: he produced a fashionable likeness; you paid him a lot of money for it. You hung it in your drawing room and precious few other people ever saw it. An idealistic young student might think very differently about the role of a painter. That was one of the tensions I set up to explore in the story.

But before we get to Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Hudson’s studio, the scene of Joe’s apprenticeship, we have to imagine what the prospects were for a boy in Derby to become either a painter or an artist in the town.

Well, firstly, there was no school of art nor established tutors or studios. Equally formidable was the lack of a market of any size within which a Derby painter (or artist) could thrive. As we have seen, the population of the town itself was small ~ only about 5,000 souls ~ and only a tiny fraction of those would ever be likely to commission a painting. Further out, in the landed estates, there were wealthy families who might. But were they enough to sustain a career and guarantee an income?

During Joe’s boyhood, the 1740’s and 50’s, painter was seen as a skilled artisan, rather like a clockmaker on a cabinet-maker. It was barely perceived of as a profession in itself. This changed as the century wore on, but if we imagine the sixteen-year-old Joe trying to convince his attorney father, who had already invested in a pricey education for his lawyer and medical sons, to invest in Joe as a painter, then you may detect yet another tension, even a family conflict. It was not much of an occupation to aspired towards at this period and in that place. Would you ever earn a decent living?

In the event, we know that Equity Wright was equitable as between his three sons: he backed Joe’s talent, but not without some argument and tussle we might imagine. It could easily be money wasted. No one in Joe’s family had any idea how a painter’s career developed.

There was a tolerably well-known painter working in Derby during Joe’s boyhood whom Equity Wright must have been aware of. His name was Thomas Smith. He was not a portrait painter: he focussed on landscapes. The gentry were always interested in two things: portraits of themselves and pictures of what they owned: country houses, rambling estates, horses. Thomas Smith of Derby (to distinguish himself from Thomas Smith of Chichester), could do the houses and estates. He painted views of the most interesting and picturesque parts of Derbyshire and the best of these were taken up to be engraved and sold as prints. He was a self-taught painter and a self-taught engraver and, as far as we know, he did not give lessons in either. In any case, doing such would only produce competition for local work that he could well do without. He did train his sons however: John Raphael Smith, who became renowned as a mezzotint engraver, (even making plates of one of Joe’s works in the 1780’s), and another son, Thomas Correggio Smith who became a miniaturist. Both sons had other trades because of the precariousness of the art market: John Raphael was originally apprenticed as a linen-draper in London.

Maxwell Craven, the prolific author on all things related to Derby and past Keeper of Antiquities at Derby Museum and Art Gallery, states that Smith was the local connoisseur of art and that in his spacious house in Bridge Gate, he built up a collection of prints and drawings by truly great artists: Correggio, Raphael, Canaletto, Poussin, Claude, Teniers, Watteau, Van Dyke, Hollar, Rubens and Durer amongst them. He also owned paintings by a host of lesser artists, mainly British contemporaries. But I know of no evidence that Joe had any access to these and I have seen no reference to Smith in any of Joe’s correspondence or elsewhere. Their times certainly overlapped: Thomas Smith did not die until 1767 when Joe was 34. By that time Joe was a portraitist and had was developing his ‘candlelight’ style. He had hardly touched landscape by that date and one might assume he would have done had Smith been an influence on him.

There had been an even earlier painter in the town. Francis Bassano was a member of a distinguished family, chiefly of musicians, established in England from Italy since the 16th century. He was entirely specialised as a ‘herald painter’ and antiquary. He travelled Derbyshire copying funeral hatchments, memorial windows, and so on from churches to sell to the relevant families. He lived in Derby, as did his younger brother the musician Christopher Bassano. Both were dead before Joe was in his teens so this was another source of expertise unavailable to him. Again, Derby being such a small place, Joe used a later Bassano, Mrs Mary Bassano, as his attractive model for Maria from Sterne which he was to paint in 1777. He knew the Bassano family well through the musical circles he moved in, being a keen amateur flautist and singer. In another connection, John Raphael Smith was to produce a mezzotint of Joe’s Maria/Mary Bassano in 1802, five years after Joe’s own death. Joe was thus linked, if only very circuitously, to both of the painterly families that preceded him in Derby.

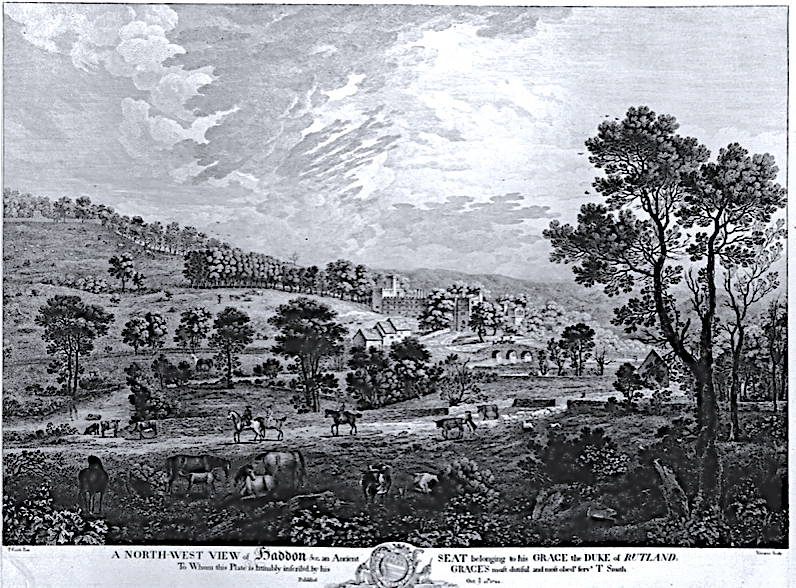

Here are two examples of Thomas Smith’s work: one published by Francis Vivares, a fellow engraver and print publisher, in 1744: A North-West View of Haddon etc., an Ancient Seat belonging to his Grace the Duke of Rutland, Haddon.

The next is a later oil painting, Landscape: Valley in Derbyshire of around 1760. It is a rather romanticised and over-blown version of Dovedale or one of the dales of the white limestone Peak. In striving to make the view picturesque it has all become rather exaggerated. This was still a long way from the period of en plein-air painting: a simple outdoor sketch would have been worked up in the studio. The foreground tree was a common device to lend scale and framing to a panoramic view: Wright was to use it often and the technique carried on right up to Turner who also used it extensively.

(Both pictures copyright of the Government Art Collection).