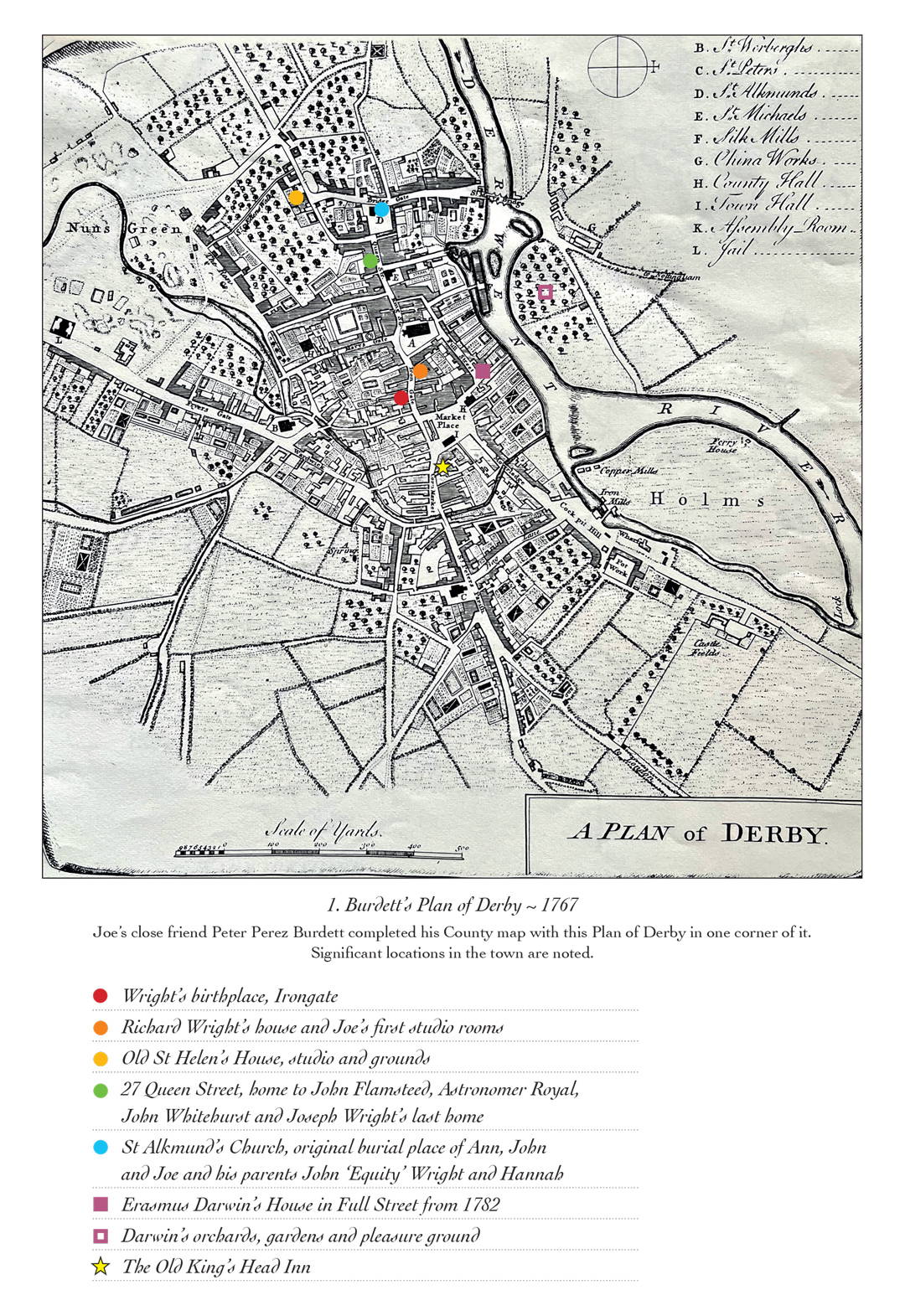

Joe was born in 1734 into a small town which had changed little since the medieval period: its size and street pattern had hardly changed for hundreds of years. It held five parishes: St Alkmund’s, St Werburgh’s, St Michael’s, St Peters and All Saints. Of these, All Saints had much the grandest church tower dating from the 1520’s. But like the other churches, it had Saxon roots, for the street Joseph Wright spent much of his life living ran by them all except St Werburgh’s: it was the ancient north-south route around which the whole town had evolved and along which the main stagecoach route between London and Manchester ran.

The population stood at about 5,000 in Joe’s time. In the election of 1741 there were only about 800 electors, all free burgesses of the town; that is the businessmen, skilled artisans and craftsmen, together with the local gentry and squires. This group had generally elected a Tory member of parliament but the pattern shifted that year when Viscount Duncannon, handily supported as the Duke of Devonshire’s son-inlaw, beat, by a very small margin, German Pole of Radbourne Hall who was not only a Tory but a firm Jacobite. Elections lasted several weeks in Joe’s time and the bribery and manipulation, (such as the creation of a surprising number of new burgesses by the Mayor Samuel Fox just prior to the vote), helped ensure a Whig victory. All this would have been familiar to Joe as he grew older: his father, John ‘Equity’ Wright was an attorney and he became the Town Clerk in 1756, retiring in ill health in 1765. As such, he was at the forefront of the town’s life, overseeing all its legal affairs, advising the town’s aldermen and having connections with all of the local gentry and landowners.

Joe was therefore born into a comfortable family. They lived in a suitably large townhouse on the western side of Iron Gate at No 28. Here they were near the centre of the town and on its more salubrious northern quarter which contained the Shire Hall, where the assizes were held, and the Guildhall where the alderman and corporation met. The southern end to town around St Peter’s and Bag Lane, (the present East Street), was poorer and much of the riverside in that area housed Derby’s manufacturies. When the plague last visited the town in 1665, it had made its first appearance in this area, in the overcrowded courts and by-lanes around it.

There was then just one bridge over the Derwent ~ St Mary’s named for its little protective bridge-chapel on the western bank. Two watercourses wove through the town and into the Derwent: the Markeaton Brook and the Littleover Brook. Numerous foot and packhorse bridges over them would have given the small town an air of a little Venice.

The town was unpaved and unlit: only the main thoroughfare along the Cornmarket to the Market Place, and up Iron Gate and Sadler Gate were properly cobbled. The hub of the town was the market: produce and livestock from outlying farms made their way here, although a separate cattle market had grown up away to the south beyond the Morledge on the riverside.

There was some important industry in the town even then. The Lombe brothers had built a water-powered silk mill on the banks of the Derwent which drove machinery they had copied from Italy. The machinery ‘threw’ silk thread to twist it into stronger and thicker staples and was one of the first ever water-powered textile mills. The Derwent powered other mills too: corn mills, flint mills (for porcelain production ~ this was here as well), paper mills, iron and copper slitting mills, forge hammers. Much of the employment of the town, was taken up in these places. But Joe attended the small Derby Grammar School, free to the sons of burgesses and freemen, sited behind St Peter’s Church. Interestingly, Joe’s elder brothers John and Richard had been sent to the expensive Repton school and from there had proceeded to enter the law and medicine. Joe was a lifelong asthmatic and was to develop an over-occupation with his health for the rest of his life ~ possibly his mother had argued to keep him close by home in his boyhood days to ensure he was looked after.

One of the most significant events of Joe’s childhood would have been the arrival of the Highland Army during the Jacobite uprising in December 1745. ‘Equity’ was no sympathiser, though many influential Tories in the town were, not least the Reverend Henry Cantell, vicar of St Alkmund’s. The Duke of Devonshire had recruited the Derbyshire Blues, a militia 600 strong, which were based in the town in readiness for any invasion, and their headquarters were a few doors down from the Wright’s at the George Inn on Iron Gate. When they heard that an army of 9-10,000 was approaching from Ashbourne, they retreated rapidly into Nottinghamshire. This was a a clear sign to families like the Wrights to abandon the town. Derby was still a predominantly a Whig town, heavily influenced by the Duke of Devonshire and his many interests. As a rising attorney considering a career serving local interests in politics and business, it would have been prudent to make himself scarce at such a time. Accordingly, the Wrights piled everything of value onto wagons and headed for Repton before they were required to billet a platoon of Highlanders. This occurred anyway: for two nights, three officers and forty men filled the empty house at 28 Iron Gate.

In the event, Charlie and his clan chieftains received word that British forces under the Duke of Cumberland were moving to cut off their path to London. Already cautious as the looked-for recruitment of new Jacobite support failed to materialise as they moved through the country, Bonnie Prince Charlie turned back to Scotland. The Wrights quietly returned.

What else might render you a picture of the Derby of Joe’s boyhood?

The town was becoming more literate and connected to the wider world: in 1732 the Derby Mercury was founded, as a weekly newspaper, its office being on Joe’s street corner between Iron Gate and Sadler Gate. Like any local newspaper it recorded the proceedings of arrest, trials and punishments, and even as a boy Joe would have been familiar with the processes of local justice. One of the town’s gaols was just behind the Guildhall in Lock-Up yard; the pillory was still set up in the Market Place for townspeople to exact their own retribution on malefactors condemned to it. The ancient place of execution ~ Windmill Pit ~ off Mill Hill Lane had been the site of the martyrdom by burning of Joan Waste two centuries before. A blind young woman, she adhered to the time-worn Protestant rituals and was made example of by a hard-line Catholic Dr Anthony Draycot, the Diocesan Chancellor, after Queen Mary had the liturgy changed. By a quirk of later fortune Joe, who was to become a firm Protestant by allegiance if not by regular practice, bought the very field of Joan’s burning. He was to buy many little parcels of property around the town and he invested in this particular close, or field, by planting a dozen trees around its perimeter. It was to bring him in handy rental which, certainly in his middle years, supplemented his earnings from painting.

Finally, there were the roads. These were poor in virtually all directions and worse in winter. It was only in 1709 that the Signpost Act obliged local corporations to put them up and to set out guide stoops ~ stone pillars like gateposts ~ to point the way at junctions in remote locations. It was just after Joe’s birth in 1735 that the first Derby-Nottingham-London stage coach was inaugurated. In 1739 there was a meeting of investors at the Old King’s Head in the Cornmarket, (the setting which I use often in Joe’s story), to create a road up the Derwent valley which was then only a track and often impassable, dependent upon the mood of the Derwent. By 1754 there was a Derby-Burton turnpike, and by 1756 a Chesterfield turnpike. With them, the stage coach companies grew up and Derby developed a number of staging inns: The Talbot, like the George, also on Iron Gate, the Virgin Inn on the Market Place, The Tiger Inn on the Cornmarket and The Bell on Sadler Gate. The railway stations of their day, a curious young boy could not fail to be attracted by the noise, bustle and excitement of a stage coach arrival or departure. They were all around him.