When you become as prominent in history as Richard Arkwright has become, there is a tendency to be reduced to a cipher, a symbol, a fixity. He has become an examination question, a figure to tick off when considering the Industrial Revolution, he is laid to rest in a box labelled, ‘Father of the Factory System,’ and that is the end of him. No more to be said.

But there is much, much more. There are two central puzzles about Richard Arkwright. The first is, how on earth did he do it? He had virtually no education, he learnt the rudiments of reading from his elder cousin Ellen. He had no money behind him: he was the last of a long line of children born to a poor tailor in Preston in 1732. He was apprenticed to a barber at age 14 and for twenty years he flogged along the highways and markets of Lancashire, buying girls’ hair, shaving the men, taking orders for wigs for both women and men both, and pulling the teeth of anyone who needed that relief. By 1767 he came across someone at an inn who knew about spinning machines and saw a tiny and improbable chance that he might get out of a trade which was leading him nowhere. From that point, he had just twenty five years left to him, though he would have reckoned on getting more: he was dead by 1792 at just 59 years.

So if the first question was how did he do it? the second is what drove him to do it? What kind of person is it that takes an idea ~ someone else’s idea in Arkwright’s case ~ and transforms into a world-leading money-making machine? And once on that road to success, where do you draw the line? At achieving a comfortable income for you and your children, or grasping for total dominance of a new global business that, once ignited, won’t stop expanding?

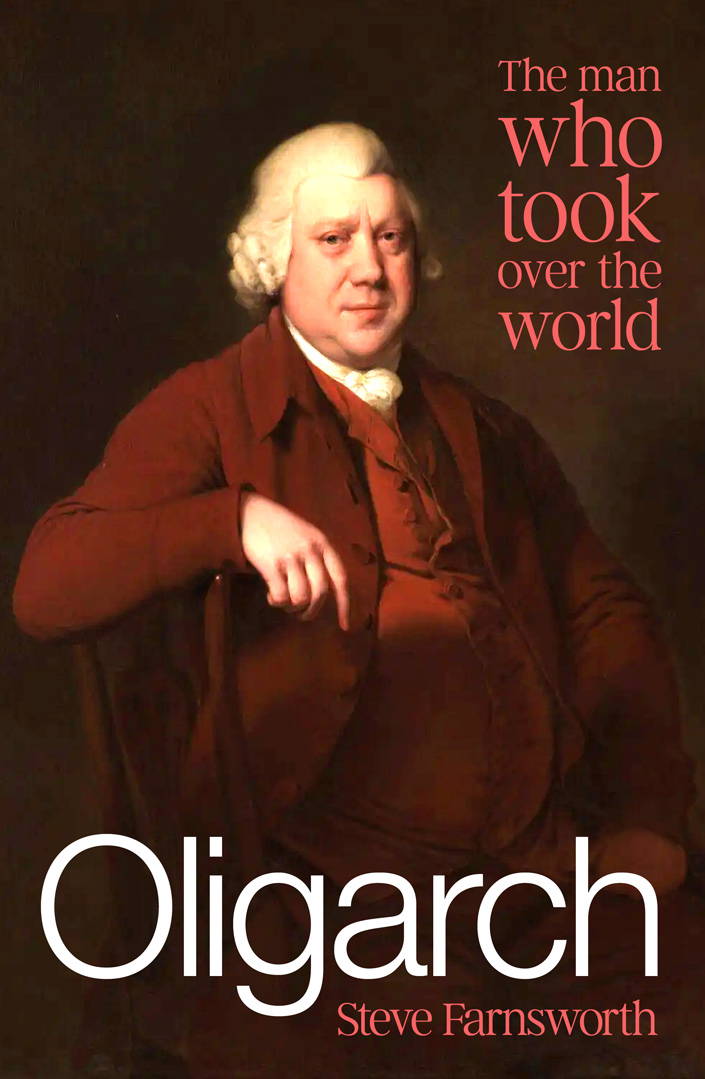

These questions take us beyond the usual portrayal of the corpulent mill-owner of Joseph Wright’s second portrait of 1790, who now presided complacently over his huge self-built business. Oligarch seeks to open up the extraordinary life of Richard Arkwright to closer inspection, to reveal the ruthlessness and remorseless ambition that impelled him, and how he came to exemplify a new kind of economic animal that Adam Smith warned of in various of his writings: the illegitimate and dangerous combination of monopoly, wealth and power in the hands of an individual, a company or a state. These are questions which are suddenly front and centre of our own times. Richard Arkwright was simply there first, testing those limits before anyone else.

Richard was almost the exact contemporary of Joseph Wright: he was born two years earlier than him and died five years earlier. Joe painted him twice, much the best portrait being painted about 1784 before he became Sir Richard. He also painted his first mill at Cromford and then Willersley Castle, the strange confection of a house-cum-fortress that he built across the Derwent from his Cromford and Masson mills, but never lived to occupy. Joe’s was a life spent in perfecting his craft and striving to find his just place in the annals of British art. He came from solid middle-class stock and died having attained, he thought, the status of ‘gentleman’. Not the lower rung of the landed gentry which had occupied that title in previous centuries, but now the man of some property but who was a definite member of the urban professional classes like lawyers, doctors, bankers and even merchants. Someone ~ was it Joe’s own instruction? ~ had ‘Efq’ carved at the end of his name on his gravestone. Richard’s rise was unparalleled, tearing past the polite social elevation that Wright obtained. From grinding poverty he was not only knighted, but made High Sheriff of the county and able, or so he is supposed to have boasted, to afford to pay off the National Debt if he felt so inclined. Son Richard, (also painted by Joe), rose even higher financially: he owned a substantial part the National Debt through his loans to the government, and became a money-lender to the gentry from Georgina, the Duchess of Devonshire, down. These social and economic elevations within the boom years of Georgian Britain, illuminate further the uniqueness of the events that occurred along this little stretch of the Derwent.